What is the Linux VFS? Understanding the Virtual File System

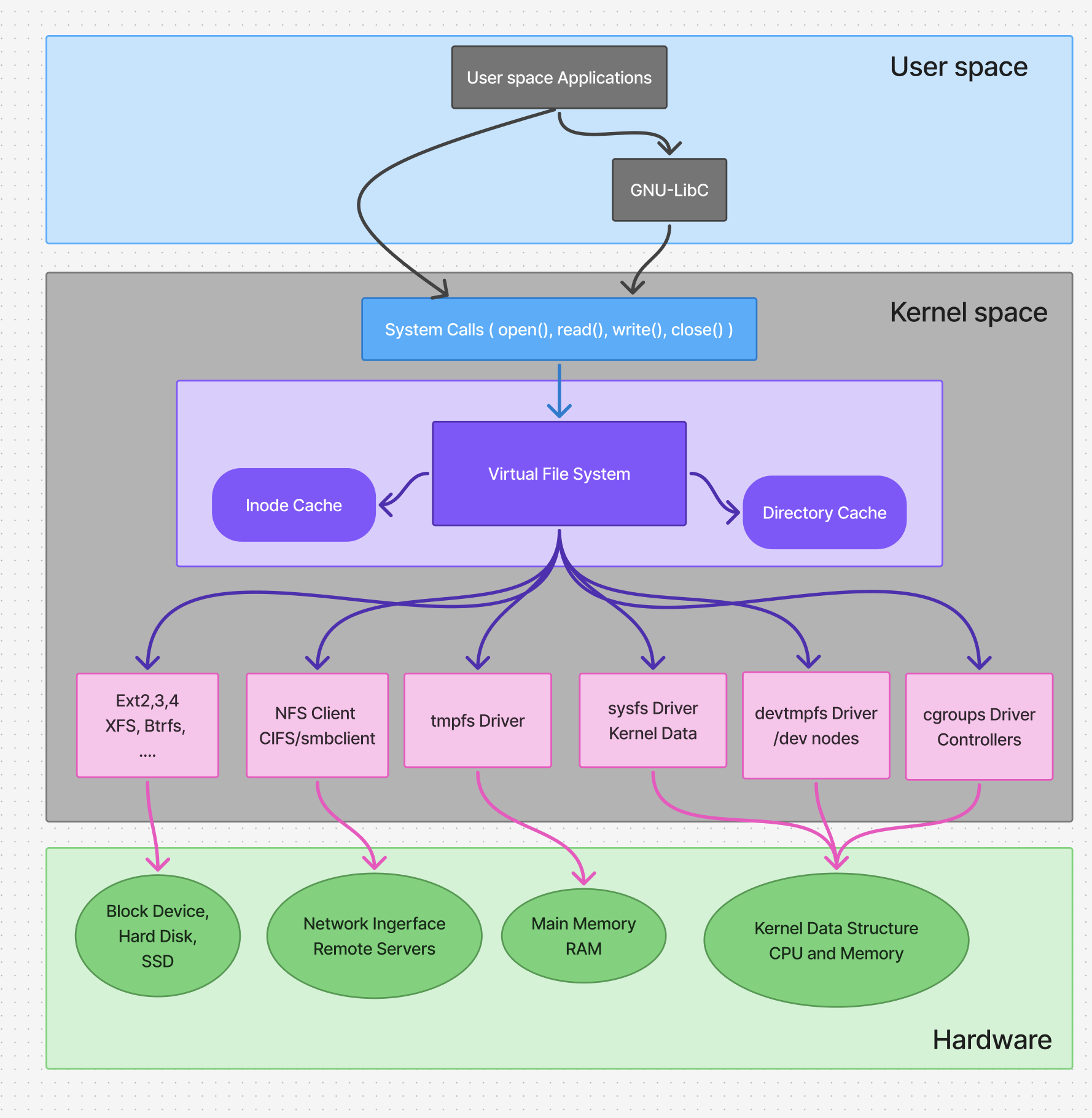

Kernen's VFS (Virtual File System) layer

An abstraction layer that hide the details of different file systems and hardware devides and present a consistent, uniform view of all files, directories, and devices to user-space programs and other parts of the kernels itself.

The Problem VFS Solves

A Linux system typically uses many different types of file systems simultaneously:

- Local Disk File Systems:

ext4,XFS,Btrfs,FAT32,NTFS - Network File Systems:

NFS,CIFS/SMB(for Windows shares) - Special/Pseudo File Systems:

procfs(/proc) - provides information about processes and system status.sysfs(/sys) - provides information about devices and drivers.tmpfs(/dev/shm,/run) - exists only in RAM.

Each of these has a different internal structure, way of storing data, and API. VFS provides a single, common interface for all of them.

The VFS does not implement the actual data storage; file system drivers do, instead the VFS defines a standard "contract" or struct of function pointers, that each file system driver must fulfill.

Key Data Structures VFS Uses:

- Superblock: mounted file system It contains info like the device it's on, block size, and pointers to the functions for reading and writing inodes.

- Inode: Holds all the metadata about the file or directory : permissions, ownership, timestamps, size, and pointers to where the actual data blocks are on the disk.

- Dentry (Directory Entry): It's a caching mechanism for translating human-readable pathnames (e.g.,

/home/user/file.txt) into inodes. - File: Represents an open file. It contains information about the interaction between a process and an open file, like the current read/write position (cursor), and mode (read, write, append). There is one

filestruct per open file, per process.

Example: Reading a File

Simple command: cat /mnt/ntfs-drive/document.txt

- The System Call:

catcalls theopen()system call with the path/mnt/ntfs-drive/document.txt. - Pathwalking & Dentry Cache: The VFS receives the call. It breaks down the path to (

/,mnt,ntfs-drive). - Routing the Request: It reaches

ntfs-drive, the dentry cache tells VFS that this directory type isntfs. VFS route all subsequent operations to the NTFS driver kernel module. - Inode Operations: VFS asks the NTFS driver to look up the inode for

document.txtin itsntfs-drivedirectory. - File Operations: VFS creates a

filestruct for this open file and returns a file descriptor (a number) to thecatprogram. - Reading Data:

catnow calls theread()system call with the file descriptor. - Universal Translation: VFS receives the

read()call. It looks up thefilestruct, which points to the inode, which points to the superblock. - Hardware Specifics: The NTFS driver translates this generic

readrequest into the specific commands needed to read the correct blocks from the NTFS-formatted USB drive. The data is fetched and returned up the chain: NTFS Driver -> VFS -> User-spacecatprogram -> displayed on your screen.

The crucial point: The cat program didn't need to know it was reading from an NTFS drive. It only interacted with the standard VFS interface (open, read, close).